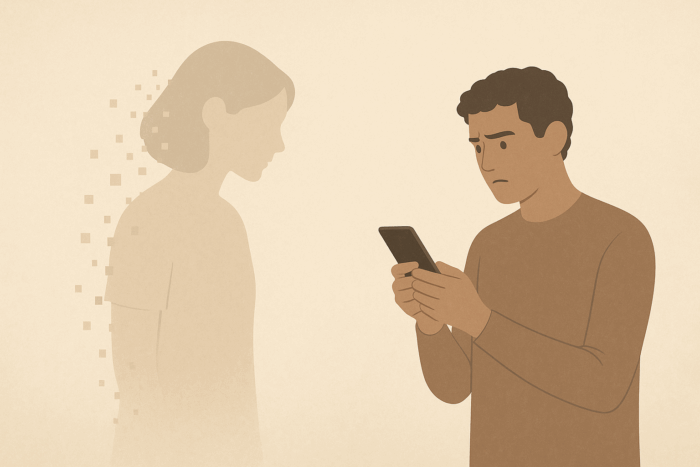

Ghosting has become one of the most emotionally disorienting behaviors in modern dating. It happens quietly; no confrontation, no closure, just silence. You’re left scrolling through unread messages, wondering what changed.

In today’s digital dating culture, ghosting is often dismissed as a side effect of too many options or too little time. But beneath the surface lies something deeper: a psychological and cultural shift in how people manage discomfort, vulnerability, and accountability.

Understanding why ghosting happens is the first step toward breaking the pattern, both for those who’ve been ghosted, and those who have ghosted someone else.

Why We Ghost

Ghosting is rarely about the person being ghosted. It’s most often a reflection of the ghoster’s emotional avoidance.

Psychologically, ghosting aligns with what researchers call avoidant coping strategies, which is the tendency to withdraw rather than confront uncomfortable emotions or interpersonal tension. According to Leary and Kowalski (1990), individuals often engage in impression management behaviors to avoid perceived social threat or embarrassment. Ghosting offers an escape hatch from the discomfort of honesty.

In attachment theory, this maps closely to the avoidant attachment style (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998). People with avoidant tendencies often struggle with emotional intimacy and conflict resolution, leading them to disconnect abruptly when situations feel too vulnerable.

For others, ghosting stems from anxiety-based avoidance, struggling with the fear of disappointing someone or being perceived negatively. Ironically, in trying to avoid emotional confrontation, the ghoster creates far greater harm through silence.

Ghosting is the act of abruptly cutting off all communication (phone, text, app messages) with someone you were dating or interacting with, with no warning or explanation.

Verywell Mind+2Tandem P

The Cultural Conditioning Behind Ghosting

While the roots of ghosting are psychological, its normalization is cultural.

The rise of digital dating has restructured social accountability. On apps, people are depersonalized into profiles where swipe decisions replace nuanced communication. The abundance of choice creates what psychologist Barry Schwartz (2004) termed the paradox of choice: too many options reduce satisfaction and increase impulsive disengagement.

In Western cultures that prize individual freedom and autonomy, emotional closure often takes a backseat to convenience. Social media amplifies this by making disengagement effortless; you can unmatch, unfollow, or block in seconds.

In contrast, some Eastern collectivist societies view relational closure as a social duty, not an emotional burden. In Japan, for instance, abrupt social withdrawal (ijime) is stigmatized because it violates harmony and respect norms (Naito, 2019).

Ghosting, then, isn’t universal, but it’s culturally permitted avoidance.

Did You Know?

Ghosting wasn’t always a dating term. It first appeared in the early 2000s in digital communication forums to describe people suddenly vanishing from online interactions, romantic or otherwise (Urban Dictionary, 2006).

It’s incredibly common: Studies show up to 78% of adults have been ghosted, and nearly 60% admit to ghosting someone (Freedman et al., 2019, Journal of Social and Personal Relationships).

Technology made it easy: The ability to block or unmatch without confrontation has normalized emotional avoidance as convenience.

Cultural norms matter: In collectivist societies, ghosting is socially discouraged due to the importance of harmony and respect. In Western societies, individualism has reduced social penalties for disengagement.

The Emotional Impact on the Ghosted

The psychological aftermath of being ghosted can mimic the symptoms of ambiguous loss; a form of grief without closure (Boss, 1999). There’s no tangible event to process, yet there’’’s a persistent sense of rejection and confusion.

Studies show that social rejection activates the same brain regions as physical pain (Eisenberger et al., 2003). This is why ghosting can feel gut-wrenching. It’s not “overreacting”; it’s a neurobiological response to perceived exclusion.

For many, ghosting triggers self-blame and rumination. The brain seeks meaning in the absence of explanation, cycling through what-if scenarios that only deepen emotional fatigue.

The truth: ghosting says more about the ghoster’s discomfort with confrontation than about your worthiness of connection.

The Cycle of Ghosting: When the Ghosted Become the Ghosters

One of the most under-discussed aspects of ghosting is reciprocal behavior. People who have been ghosted often begin to ghost others, either out of emotional self-protection, or learned normalization.

This cycle is sustained by three mechanisms:

- Emotional avoidance: Repeating the pattern feels safer than risking vulnerability.

- Cognitive dissonance: People rationalize ghosting as “necessary” because it was done to them.

- Desensitization: The more ghosting occurs culturally, the less empathy individuals feel for those they ghost.

Breaking this cycle requires what psychologists call emotional differentiation; or recognizing your own emotional patterns before they become reflexive behaviors (Siegel, 2012).

How to Respond to Ghosting Without Losing Yourself

Being ghosted hurts, but how you respond determines whether the experience hardens or grows you.

Five grounded ways to respond:

- Pause the self-blame. Silence isn’t proof of inadequacy. It’s evidence of avoidance.

- Resist the chase. Seeking closure from someone unwilling to offer it only prolongs the power imbalance.

- Name the emotion. Labeling feelings (hurt, confusion, anger) reduces their intensity by engaging rational processing (Lieberman et al., 2007).

- Set a communication boundary. Choose not to ghost others. Explain briefly, exit kindly.

- Reflect, don’t repeat. Ask: “What does this teach me about my own communication patterns?”

Technology’s Role in Fixing What It Broke

If technology amplified ghosting, it also holds the key to reducing it.

Some modern dating platforms, like Swept Dating, are creating tools that make ghosting socially visible and emotionally accountable with features like connection feedback opportunities and visible digital “badges”, that encourage users to follow through on communication instead of disappearing.

By embedding empathy and responsibility into digital design, these platforms are addressing ghosting not as a moral flaw, but as a behavioral feedback loop that can be interrupted through awareness and accountability.

Related Content: Ghosting: How Swept Dating is Transforming Communication in Online Dating

Related Content: Swept Dating CEO Rob Kennedy Talks Ghosting, AI, and Fixing Modern Dating

Understanding to End the Silence

Ghosting thrives in a culture that rewards avoidance. But the more we understand its psychological roots, the more power we gain to stop repeating it.

When we choose courage over comfort, clarity over silence, we don’t just change dating, we change the emotional norms of communication itself.

If you’re ready to date differently, explore how Swept Dating is helping users build authentic accountability and reduce ghosting through mindful design.

References

Boss, P. (1999). Ambiguous loss: Learning to live with unresolved grief. Harvard University Press.

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). Guilford Press.

Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? Science, 302(5643), 290–292.

Leary, M. R., & Kowalski, R. M. (1990). Impression management: A literature review and two-component model. Psychological Bulletin, 107(1), 34–47.

Lieberman, M. D., et al. (2007). Putting feelings into words: Affect labeling disrupts amygdala activity in response to affective stimuli. Psychological Science, 18(5), 421–428.

Naito, T. (2019). Cultural implications of interpersonal avoidance in Japan. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 22(3), 205–214.

Schwartz, B. (2004). The paradox of choice: Why more is less. Harper Perennial.

Siegel, D. J. (2012). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.